An interactive website built as a capstone project for the MS in Data Analysis and Visualization degree program at The CUNY Graduate Center.

The word “billion” is a mathematical abstraction related to “big,” but it is difficult to understand the vast difference in value between one million and one billion; even harder to understand the vast difference in purchasing power between one billion dollars, and the average U.S. yearly income. Perhaps most difficult to conceive of is what that purchasing power and huge mass of capital translates to in terms of power. This project blends design, text, facts, and figures into an interactive narrative website that helps the user better understand their position in relation to extreme wealth: https://whatdoesonebilliondollarslooklike.website/

NYC's GreenThumb Community Gardens /

Interactive web map showing names locations and operating hours of NYC’s GreenThumb community gardens.

Independent Contractors vs. Deliveristas: Shaping and Mobilizing Worker Consciousness in the Digital Factory /

A Gramscian analysis of efforts to organize and mobilize app-based “gig” workers for Gramsci and His Legacy, CUNY Graduate Center, Spring 2023.

Read the paper here: Independent Contractors vs. Deliveristas

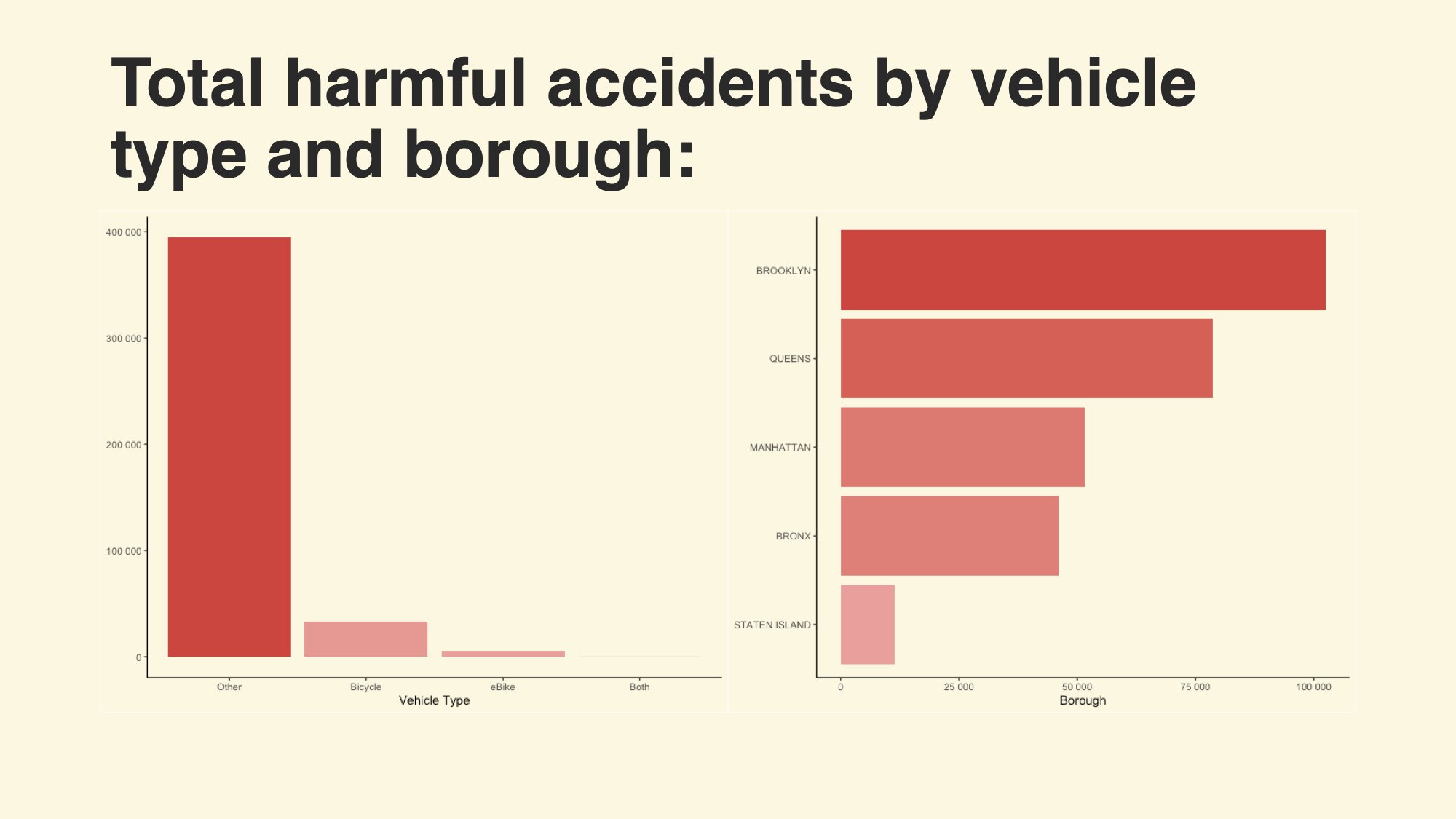

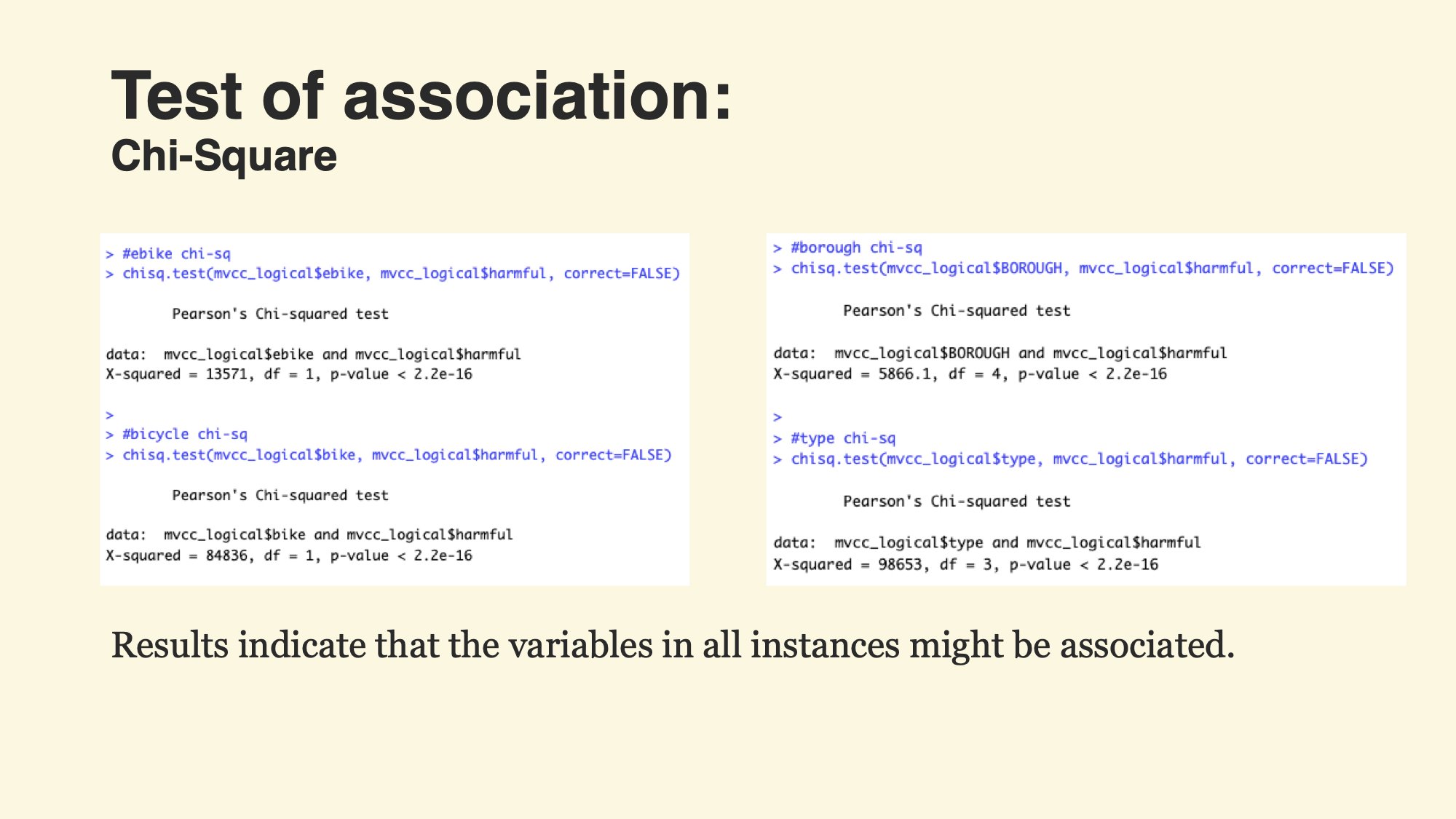

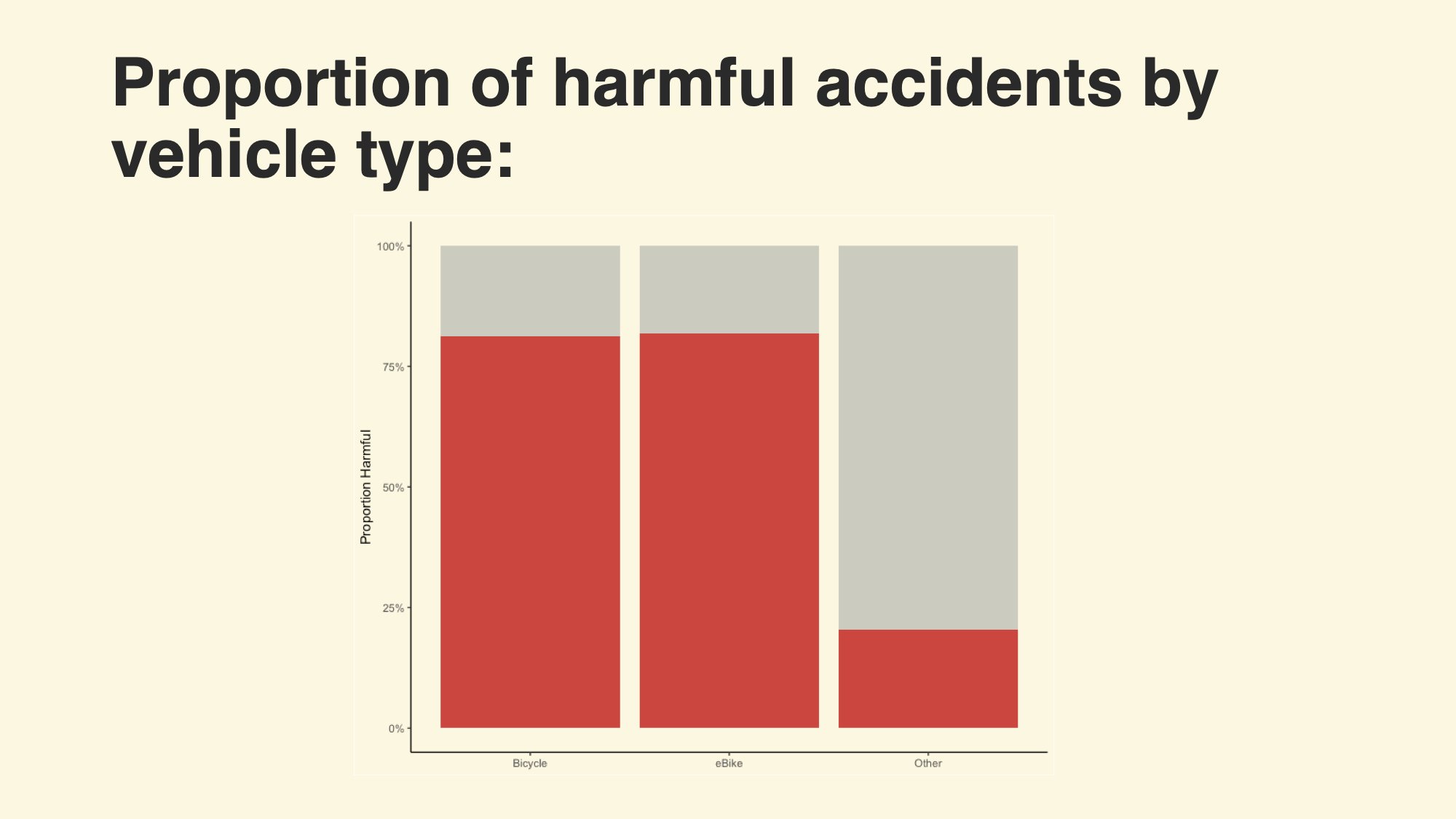

E-Bike Safety in NYC /

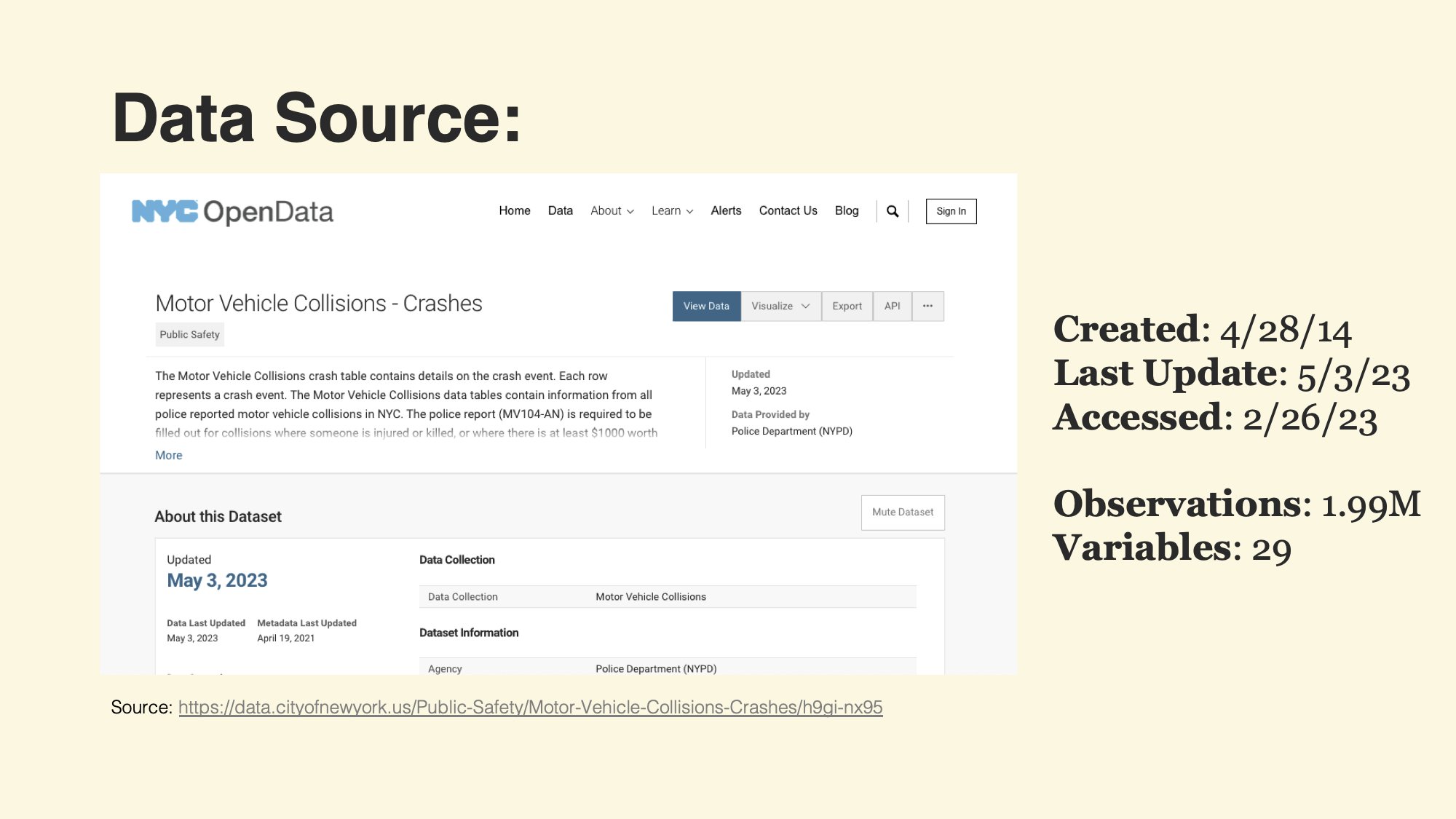

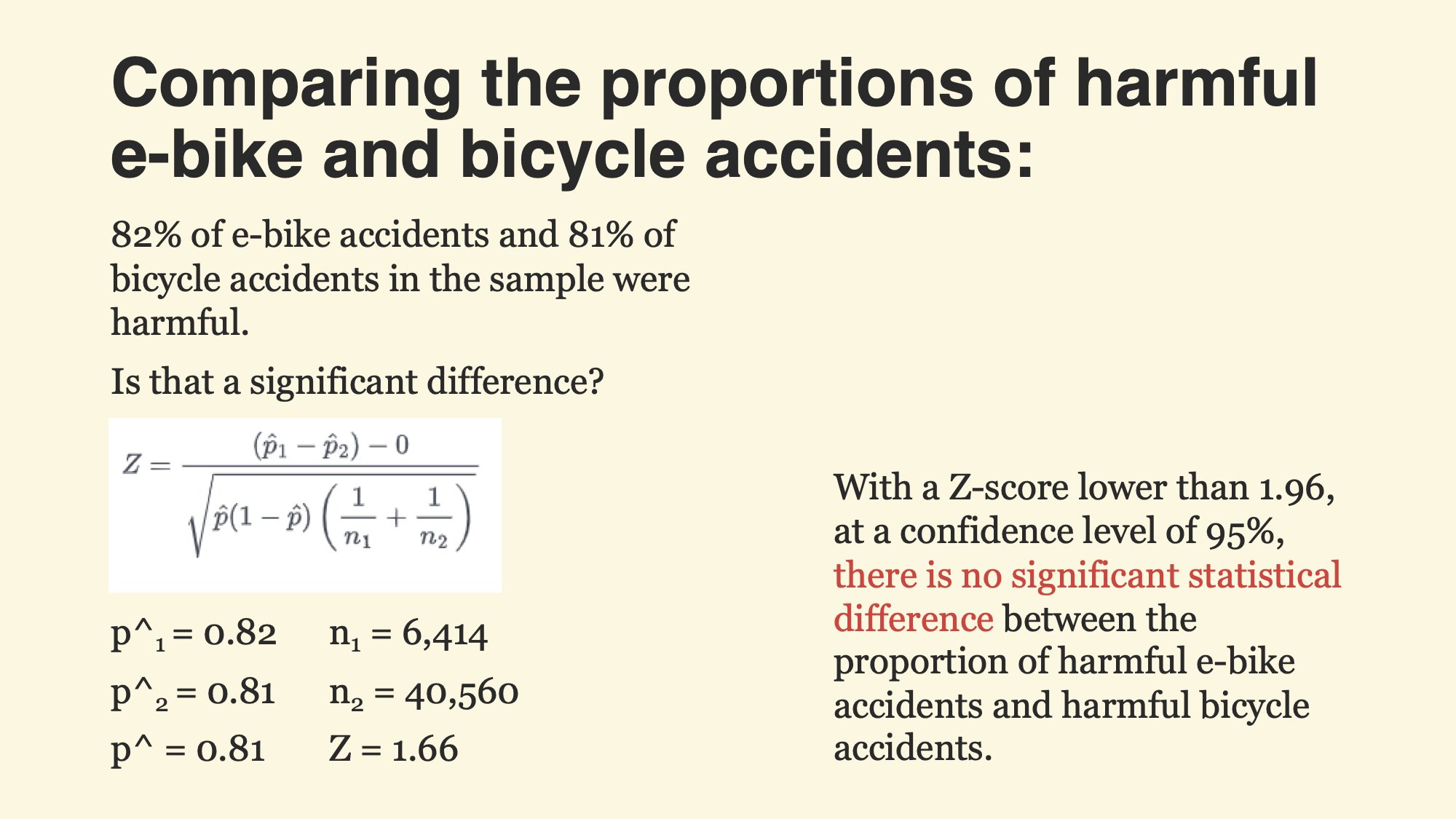

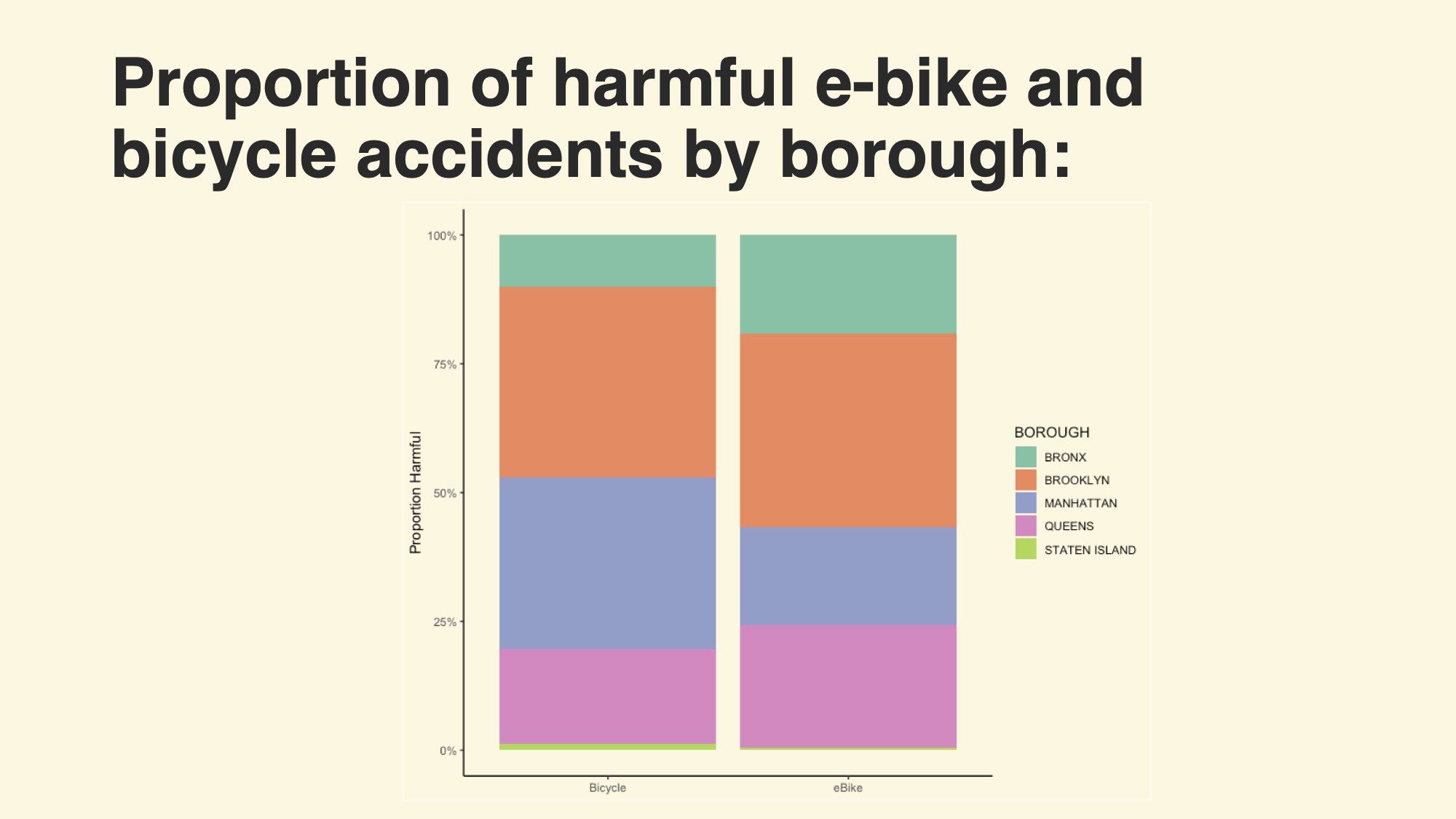

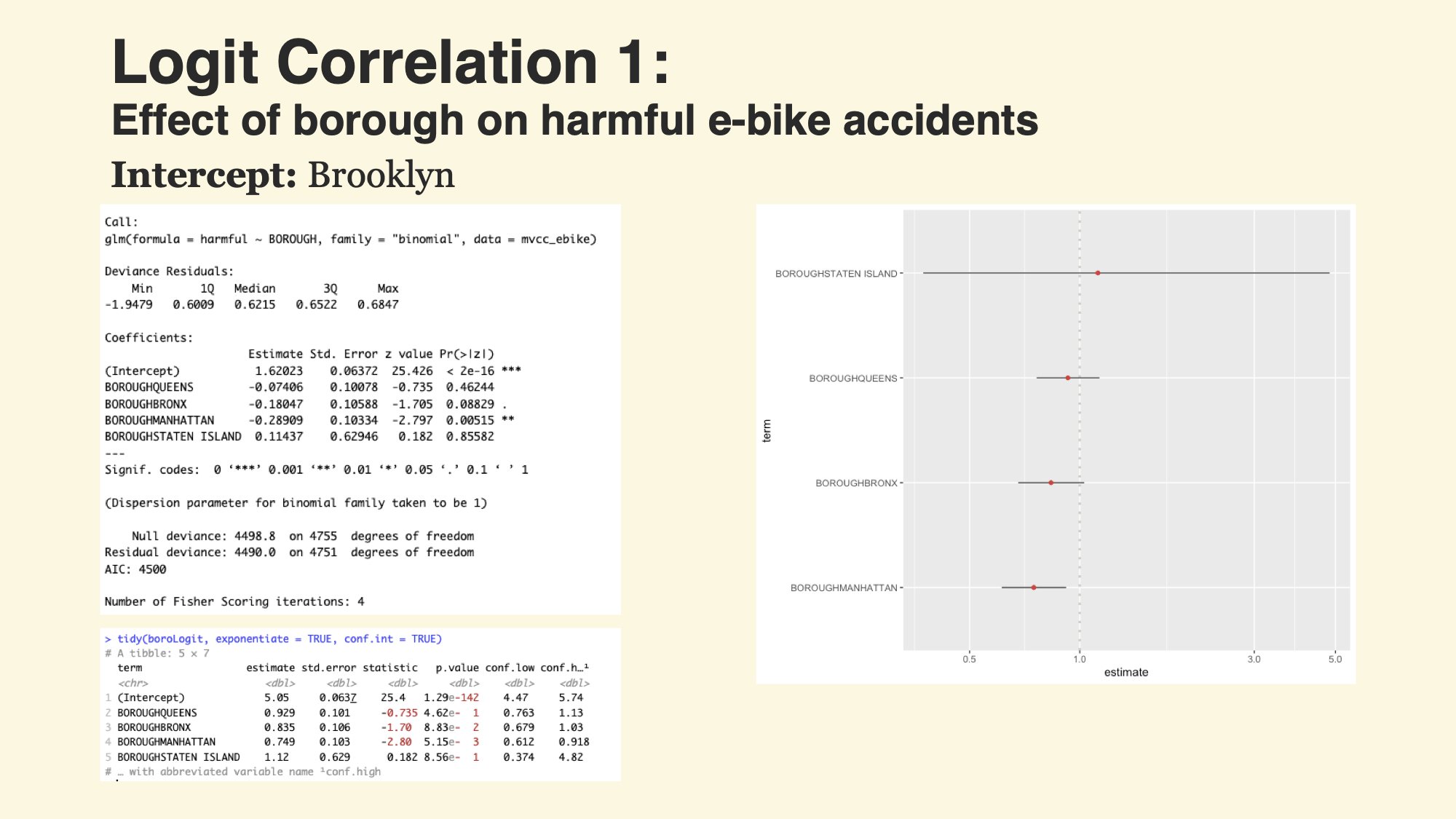

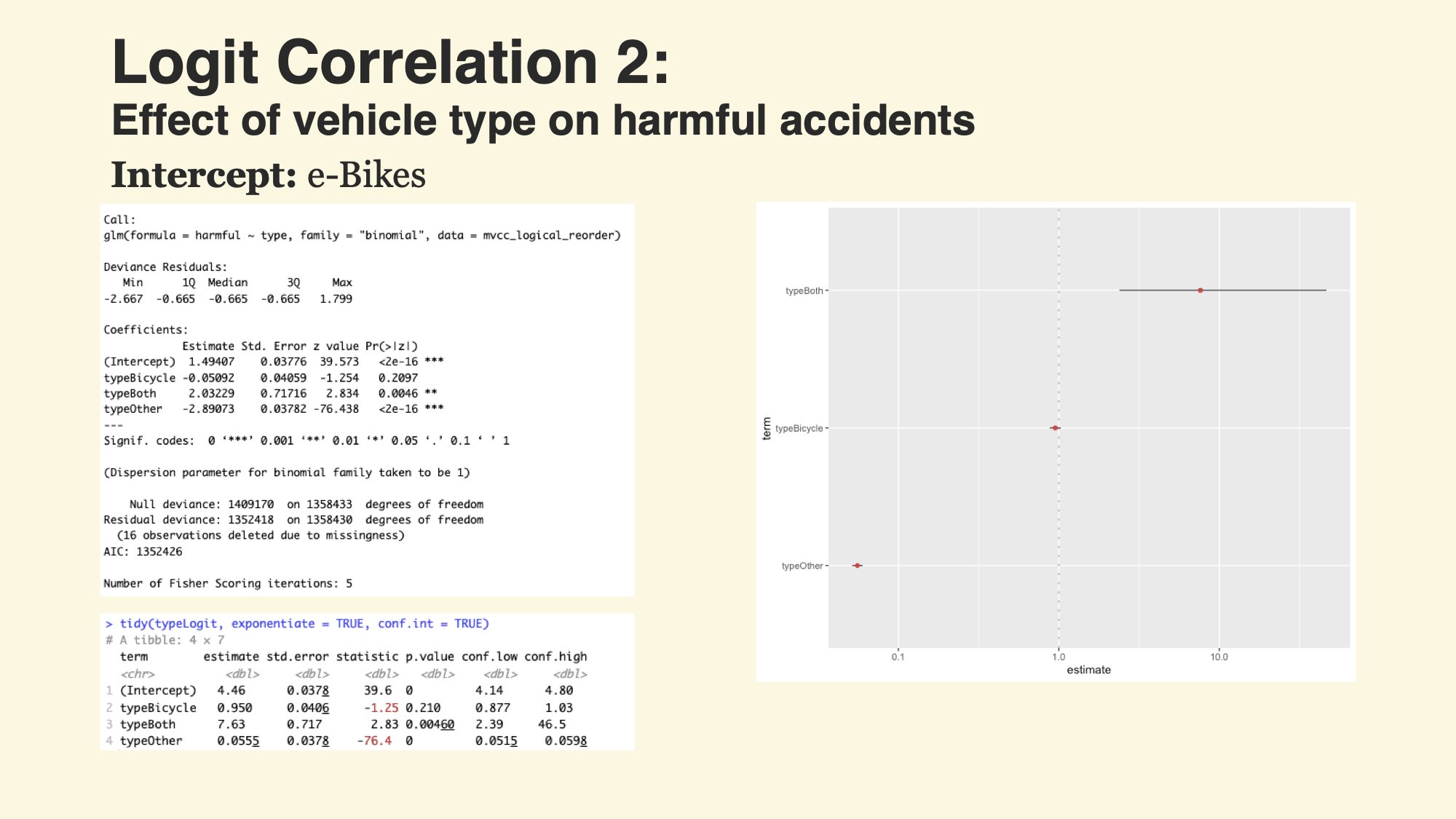

Slides accompanying a presentation of my statistical analysis of publicly available E-Bike accident data in NYC. Some conclusions could be drawn from the existing data, however, due to the circumstances of the collection of data, and specifically what information is collected and when/why it is being collected (as the result of a crash that involved the police), we lack enough data to draw any conclusions of significance.

Facebook, the Metaverse, and the Cyberspatial Fix /

A Marxist analysis of Facebook’s (Meta) investment in “Web3” for Theory and Practice of Contemporary Capitalism, CUNY Graduate Center, Fall 2022.

Read the paper here: Facebook, the Metaverse, and the Cyberspatial Fix

How Big is Big Government?: Exploring Trends in Public Employment /

Interactive website allowing exploration of public employment in the U.S. by state, and in relation to other socioeconomic data.

Visualizing NYC Broadband /

NYC’s Network Landscape

The Political Economy of NYC Broadband

Whether it’s finding a job, receiving education, looking for a home, or otherwise fully participating in modern civic, cultural, and economic life, a high-speed internet connection is a requirement. Yet many New Yorkers don’t have a reliable connection to the internet at home. The “digital divide” between those with a connection and those without was thrown into stark relief during the early days of the COVID lockdown, when some could learn, work, and access healthcare from the safety of their homes, while others had to risk their own health and the health of others to access basic necessities—or go without. But this divide existed prior to the crisis, and it will be with us long after unless it is addressed head-on. This is not a technological problem—the technology exists as does the capacity to build and maintain it. This is a political problem, one grounded in the question of whose interests the construction of infrastructure serves. To solve this problem, we need to look at the economic and historical factors that lead to our current moment.

Although there are many ways to get online (e.g. data-based cellular service, WiFi networks, DSL, copper telephone lines) the gold standard for high-speeds and reliability is a hard-wired broadband connection. “Broadband” qualifying speed is defined by the FCC as 25 megabits per second for downloading files, and 3 megabits per second for uploading. This is quite low, as even a single video call requires more bandwidth.1 For the purposes of this study, I use the term “broadband” to refer to in-home connections meeting this minimum speed requirement (as opposed to cellular or WiFi networks). Given the lax, frankly inadequate, standards of qualifying “broadband,” anything that doesn’t meet that criteria is not a serious solution to the problem at hand.

Although there are a number of different private and public internet networks in operation in New York City (some of which I will expand upon later) the provision of last-mile, in-home internet service is largely dominated by a “Big 3” of for-profit internet service providers (ISPs): Verizon, Optimum, and Spectrum. The private, for-profit provision of internet service has contributed to the digital divide in two major ways: 1) High prices mean services are unaffordable for many New Yorkers and 2) even if some New Yorkers can afford services, if the providers don’t think there is a high enough density of potential customers in a given area, they won’t have an incentive to build and maintain broadband infrastructure in those areas. Simply put, if these companies can’t make a profit in the arrangement, then service won’t be provided.

But broadband provision isn’t happening in a free market vacuum. The state plays a role in allowing providers access to the market and access to existing public infrastructure. Historical factors, including pre-existing networks, and economic and business needs of various actors have shaped where, why, and how broadband has been built and supplied. To illuminate the study of broadband revenue and spending in the visualization above, it is helpful to have a better understanding of the current internet network landscape of NYC. Below, I offer some additional information on the current networks in operation in New York City, the regulatory and financial arrangements under which they operate, and some of the private, state, and civic groups involved in efforts to direct the construction of these systems.

Franchise Agreements

In order to operate in NYC, telecommunications companies must enter into a contract with the City, known as a “franchise agreement.” For the privilege to operate, the franchisee must abide by certain rules laid out in this contract, and they must pay the City a percentage of their revenue. These contracts are overseen by, and fees are paid to, the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Revenue generated from these franchises is then distributed back into the City’s overall budget. Telecom providers are regulated by agreements based on the technology of the networks they operate, including Information Service franchises, Mobile Telecom franchises, and Cable TV franchises, among others.2

The Big 3 providers all operate their internet services via Cable TV franchises, so their broadband provision is governed under a relationship dictated by a preceding infrastructural layer. Optimum’s franchise agreement was signed in 2011 with Cablevision, now Altice USA, Inc., covering the Bronx and Brooklyn, and expired in 2018. Spectrum’s franchise agreement was signed in 2011 with Time Warner Entertainment Company, L.P., now Charter Communications, Inc., covering Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and Manhattan, and expired in 2018. Verizon New York, Inc. signed a citywide agreement in 2008 that expired in 2020. It was the existing coaxial cable networks connected to residences throughout the city that allowed these providers to simply supply last-mile internet connections by combining them with their preexisting networks.

Cable TV franchise agreements require that the providers make service available to any resident within their area of operation, but in practice this requirement has not been met by any of the Big 3. Franchise fees of 5% of gross revenue collected in the franchise territory are to be paid quarterly. There are additional regulatory terms laid out in these agreements including provisions on maintenance, customer service, public access, and insurance. As an enforcement mechanism, these contracts all describe specific terms by which the City can take ownership of infrastructure in the case of non-compliance by the franchisee with the terms of the franchise.3

However, enforcement of these agreements have proven difficult at best, or low priority at worst. Spectrum and Optimum are both currently operating under the terms of expired agreements pending renewal since 2018, despite both violating the terms of their original franchise. In 2019 DoITT announced an audit of Altice for seemingly overcharging Spectrum customers in NYC in violation of their franchise, but it is unclear if and how that issue was resolved.4 In 2017 The New York State Attorney General initiated a lawsuit against Charter, alleging they were advertising internet speeds up to 80% faster than the service they delivered to customers (which would also be in violation of their franchise agreement). Charter paid a $174.2M settlement to resolve that case with the State at the end of 2018.5 In a separate case Charter was found to have been misleading State regulators about where new service was being offered, and was almost kicked out of the state entirely as a result.6 7 The City sued Verizon in 2017 for failing to meet the citywide roll-out of its fiber-optic network required by the terms of its franchise agreement. This case was settled in 2020, with Verizon promising to build out a network with the potential to reach an additional 500,000 units by 2023.8 Verizon also received a temporary extension of its expired franchise agreement as part of the settlement.

Other Networks

Aside from the Big 3 there are a number of other privately and publicly owned telecommunications networks operating in NYC. Although the number and variety is too large to explore here in great detail, I’d like to touch on a few of them to help illustrate the larger network landscape. There are a number of “dark fiber” networks that build and lease large fiber-optic networks used for exclusive traffic by large institutions like government agencies, industry, and universities, operating under Information Services franchise agreements.9 These include companies like Stealth Communications Services, Pilot Fiber NY, and the largest, Crown Castle Fiber (formerly Light Tower).10 LinkNYC, operated by City Bridge, a consortium of technology and communications groups including a subsidiary of Alphabet/Google, operates a network of WiFi kiosks, built on top of a former payphone network, that make money through advertising and data harvesting. Despite failing to install even 50% of the kiosks required by their franchise agreement, and failing to pay an estimated $60M in franchise fees, as well as the original kiosks being plagued by privacy complaints from civil rights organizations, the consortium behind LinkNYC was recently awarded a new franchise agreement to instal 5G wireless towers throughout the city as Link5G. The hardware connections in these new towers will be leased to other telecoms seeking 5G transmitters, opening up a new stream of revenue for the consortium.11 Cellular and other telephone operators also build and operate infrastructure throughout the city.

The City itself has also constructed a number of networks. Pitched as a response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, in 2004 the City announced plans to create an internal WiFi network for use primarily by first responders. Debuting in 2009, the New York City Wireless Network (NYCWiN) was built and operated by Northrop Grumman, a military contractor, for an initial investment of $500M, and was primarily used to connect “smart” traffic lights and other administrative and surveillance infrastructure.12 The system was poorly maintained and underutilized, although Northrop Grumman eventually received in the area of $900M in contracts related to the construction, maintenance, and operating contracts of NYCWin.13 DoITT announced in March 2022 that NYCWin would be decommissioned by 2023.14 The NYPD claims to operate “third-largest [high-bandwidth] network in New York City, and the largest not owned by telephone companies”15 (which, if accurate, means their network is bigger than one of the Big 3’s). The FDNY has built and operates a separate large-scale network.16 And DoITT itself operates CityNet, “New York’s institutional fiber network, which provides the data communications backbone for City agencies, entities and more than 300,000 employees. The proprietary network is comprised of a secure dark fiber network that interconnects city agencies, hosts citywide applications, and provides Internet-based services citywide.”17 There are more, these are just a few examples of the networks already owned and operated at the municipal level in NYC.

New York City is also home to an increasing number of wireless “mesh” or “community” networks. These include Red Hook WiFi, The Hunts Point Community Network, and NYC Mesh. Mesh networks use hardwired routers connected to the internet to beam WiFi signals to other “node” transmitters, usually installed on rooftops by landlords, tenants, or businesses donating installation sites. This then creates a WiFi network within range of any one of these transmitters, which, depending on the governance of the network, is often shared for free. These networks are usually run as (or by) a non-profit entity, and rely on a mixture of grants, corporate philanthropy, and volunteer donations (of labor, cash, hardware, and real estate) to fund their operations, including connecting to the internet.18 19 20

Lastly, it should be noted that as a historical hub of economic and communications exchange, New York City is also home to a number of pieces of infrastructure connected to the large global communications network that is the internet. The City hosts a number of carrier hotels, internet exchange points, and data centers that facilitate the connection of the disparate networks owned by various consortiums of public and private operators, nationally and internationally, and stitches them into the mostly cohesive global network we call the “internet.” These are largely sited in close proximity to the Financial District, some in former telephone switching stations that facilitated earlier financial market activity, others built more recently to provide the bandwidth needed for computer-aided high frequency trading.21 Many transatlantic communications cables connect within close proximity to NYC, and Alphabet/Google, which has an office in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, is set to go online with their newly laid “Grace Hopper” cable connecting New York to Cornwall, UK, and Bilbao, Spain, sometime this year.22

Internet Master Plan (IMP)

In January 2020, in the final year of Bill de Blasio’s term as mayor, the Mayor’s Office of the Chief Technology Officer released their “New York City Internet Master Plan.”23 Compiled by the Mayor’s CTO, former Microsoft Director of Technology & Civic Innovation John Paul Farmer,24 and led by a team consisting of private industry consultants and tech policy experts, the plan hopes to achieve universal broadband coverage through City investment in middle-mile “open access” broadband infrastructure. It is an effort to foster competition to the Big 3 by absorbing network construction costs. The report states: “Leveraging City real estate assets and public rights-of-way will allow network operators to extend fiber optic infrastructure from the intersection to a pole or building and deliver service using any of a number of potential technologies.” In other words, the plan is for the City to use public investment to build infrastructure that will allow greater market-based competition for the private-provision of last-mile service. As of the end of the former mayor’s term, a $157 million dollar investment in the IMP was announced, but that money may not have been distributed. A handful of Requests For Proposals (RFPs) were also issued in early 2021, to begin implementation of the IMP through City contracts.25 The status of the IMP is unclear under the administration of de Blasio’s successor, Eric Adams, although it should be noted that former CTO Farmer has been replaced, and Adams is restructuring the organization of City technology agencies under a newly formed “Office of Technology and Innovation.” This office is currently touting the Link5G rollout (discussed above) as the immediate solution to the digital divide.26

Internet for All Coalition

The Internet for All coalition is a collection of civil society groups organizing together to push for the construction of a “publicly owned, fully-unionized municipal broadband provider”27 in New York City. The constituent organizations involved in a public launch of the coalition in early 2021 included IBEW Local-3 (representing striking Charter Spectrum cable line workers), VOCAL-NY (specifically member-organizers of their Homlessness Union), MORE (a rank and file caucus within NYC’s teachers’ union), and NYC-DSA Tech Action Working Group (a volunteer-led socialist political organization). Each of the groups involved were engaged individually in organizing work around internet infrastructure and access, and the coalition formed largely in response to the acute need for access spurred by COVID social distancing protocols. The group issued their “Municipal Broadband Network Report,”28 authored by NYC-DSA Tech Action Working Group, in July 2021. This report collects research on the digital divide and ISP malfeasance in NYC, and examines the feasibility of a model municipal-broadband network in NYC, including a phased roll-out plan, estimated costs, and possible financing options.

Challenging Broadband Ideology

As my visualization shows, many New Yorkers lack a reliable internet connection because it isn’t profitable for the three big private ISPs to ensure they have one. Those companies pay a small fee to operate in NYC, but in turn the City ends up paying more for telecommunications access than it collects in revenue. A deeper exploration of the network landscape of NYC reveals that although the City has a stated goal of achieving universal internet access for residents, the policy they have implemented historically and the policy suggestions that have been made for the future center on using state investment to stimulate market competition for the private provision of at-home internet. Despite past investments in various publicly owned networks for internal use, there seems to be little to no appetite to extend that investment towards the direct provision of internet access to New Yorkers.

This lack of political imagination or will is in line with a largely unchallenged bipartisan ideology of neoliberalism that has come to dominate United States—and to an extent, global—governance at the turn of the twenty-first century. The origins and spread of this market-first governing model are long, complicated, and contested, but it is broadly characterized by a belief in the “inefficiency” of the state to provide services, and an attendant desire to shift these responsibilities to private actors. It was this same ideology, enacted on the federal level, that led to the birth of the contemporary commercial internet through the privatization of the government-funded NSF Net “backbone” in 1994.29 At the scale of the city, author Aaron Shapiro describes this trend as “austerity urbansim,” and ties it directly to technology and the rise of the concept of the “smart city.”: “The smart city emerges in mainstream discourse and political rhetoric as a set of technical fixes to what is ultimately the ongoing crisis in the welfare of society’s most vulnerable—an upward redistribution of resources from public agencies and institutions to corporations, their investors, and their shareholders.”30 Here he is referring specifically to the technology vendors supplying various apps, platforms, and algorithms of state administration, but you can easily extend this understanding to encompass the private provision of the network infrastructure on which these “smart” tools operate.

The goal of this project is to challenge this dominant ideology here in New York City. The galling divide in access along economic lines, and their repeated violations of the terms of their franchise agreements, puts the lie to any claims of “efficiency” on the part of private ISPs. And even if one believes in reduced government spending and the efficacy of austerity measures, the economic analysis shared above demonstrates that current policy has the City government throwing good money after bad, playing the role of tenant to the telecom rentiers, spending too much on services and building no form of state equity or capacity in exchange. If the government is serious about bridging the digital divide, it is clear that the current approach isn’t working. The state must instead embrace its historic role in building and maintaining the foundational infrastructure of social reproduction. But to effect that change will take pressure from below, pushing back against the monied interests who gain financially from the current arrangement. Infrastructure is a social construct as much as it is a technical one. It is only by understanding the provision of broadband not as an economic problem, or a technical problem, but rather as a political problem, that we can then rise to meet this challenge and address it on the proper terrain—the terrain of mass political action.

Notes

Gershgorn, Dave. “Minimum broadband speeds are likely too low, government watchdog says.” The Verge. July 8, 2021.

Franchise Process – DoITT. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doitt/business/franchise-process.page

Cable TV Franchises – DoITT. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doitt/business/cable-tv-franchises.page

Gartland, Michael. “Cable company Altice overcharged customers, city alleges.” New York Daily News. August, 11, 2019.

Gartenberg, Chaim. “Charter-Spectrum reaches $174.2 million settlement in New York AG’s speed fraud lawsuit.“ The Verge. December 18, 2018.

Carman, Ashley. “Spectrum internet is getting kicked out of New York.” The Verge. July 27, 2018.

Bode, Karl. “Charter Spectrum Won’t Get Kicked Out Of New York State After ISP Promises To Suck Less.” Techdirt. April 19, 2019.

Brodkin, Jon. “Verizon wiring up 500K homes with FiOS to settle years-long fight with NYC.” Ars Technica. November 30, 2020.

Burrington, Ingrid. Networks of New York: An Illustrated Field Guide to Urban Internet Infrastructure. Melville House, 2016.

Information Services Franchises – DoITT. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doitt/business/information-services-franchises.page

Sandoval, Gabriel and Joshua McWhirter. Big Tech Pays to Supersize LinkNYC and Revive Broken Promise to Bridge Digital Divide.” THE CITY. April 27, 2022.

Burrington.

Calder, Rich. “NYC tech agency failed to oversee wireless network: report.” New York Post. June 21, 2019.

Office of Technology and Innovation Testimony Before the City Council Committees on Land Use and Technology. March 23, 2022.

Technology – NYPD. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/about/about-nypd/equipment-tech/technology.page

DOI Investigation Into The City’s Program To Overhaul The 911 System Reveals Significant Mismanagement At The Root Of Cost Overruns And Delays. February 6, 2015.

CityNet – DoITT. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doitt/agencies/citynet.page

Grants – NYC Mesh. https://www.nycmesh.net/sponsors

Partners & Donors – Red Hook Initiative. https://rhicenter.org/who-we-are/partners-donors/

Hunts Point Partners. https://www.huntspoint.nyc/partners/

Burrington.

Hamilton, Isobel Asher “Google Finishes Giant Grace Hopper Undersea Internet Cable, NY to UK.” Sep 15, 2021.

The New York City Internet Master Plan. January, 2020.

Mayor de Blasio Appoints John Paul Farmer as Chief Technology Officer | City of New York. April 23, 2019.

Kim, J.D. “A Complete Timeline of the Internet Master Plan under Mayor Bill de Blasio.” Technology Law NYC. January 7, 2022.

Mayor Adams Creates More Efficient Government by Consolidating City Tech Agencies Under New Office of Technology and Innovation. January 19, 2022.

Internet for All NYC. https://internetforall.nyc/

DSA Tech Action Working Group Municipal Broadband Network Report. July, 2021.

Lewis, Peter. “US Begins Privatizing Internet’s Operations.” The New York Times. October 24, 1994.

Shapiro, Aaron. Design, Control, Predict: Logistical Governance in the Smart City. University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

In Dreams I Walk With You /

Since early 2019, I’ve been keeping a dream journal on my phone. The original impetus was to better remember my dreams—to be able to hold on to those fleeting fragments I remembered upon waking, and, over time, to be more conscious of them. The practice of logging did in fact help me remember more of my dreams with more frequency, but until now I haven’t spent any time revisiting those entries.

For this project, In Dreams I Walk With You, I used data visualization to explore one particular aspect of those dreams: who I spend time with on the astral plane. The title for this project is taken from the lyrics of the song “In Dreams,” by Roy Orbison, in which the narrator describes a relationship with the love of his life that exists “only in dreams”—in his waking life they are separated. For myself, and I imagine many others, the relationships in my dreams are not tied to the temporal reality of my day to day. In dreams I spend time with childhood friends, former lovers, family members living and dead, strangers, and people near and far from me in real life.

My goal was to make visible these dream relationships, and to complement them with information about our waking relationship. Through this combination—and interactive functions that allow the viewer to explore—I hope to paint a picture of my conscious and subconscious relationships, and the overlaps or gulf between them. Ultimately it’s a self-portrait; more art than science.

Best viewed in full-screen mode, or here.

Logic Magazine: In Defense of the Irrational /

Testimony submitted to NY City Council on the Digital Divide - 10/13/2020 /

ORGANIZER

NEW YORK CITY DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISTS OF AMERICA (NYC-DSA)

TECH ACTION WORKING GROUP

BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON TECHNOLOGY

& SUBCOMMITTEE ON ZONING AND FRANCHISE

NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL

FOR A HEARING CONCERNING

OVERSIGHT – BROADBAND AND THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

PRESENTED OCTOBER 13, 2020

Microsoft needs to stop selling surveillance to the NYPD /

Left Forum 2019 /

I'll be speaking at Left Forum 2019 about art, institutions, platforms, technology, and politics

Tech Organizing Against Amazon HQ2 /

Julia Salazar vs. Big Tech /

Left Forum 2018: Towards an Organized Tech Industry—Part Two /

Can We Design a More Perfect Design Union?: Recap Video /

Can We Design a More Perfect Design Union? #1 /

I'm honored to be appearing on this panel/workshop addressing the need to organize freelance workers, and developing strategies for doing so!

Mmuseumm: Season 6 /

I helped manage the launch of Mmuseumm 2018, opening Thursday, April 26

The Internet We Want /

The NYC-DSA Tech Action Working group I help organize cohosted the panel below at Verso Books on 12.16.17. We are attempting to sketch out a Left vision for the internet and other new technology—one that puts people over profits. In the video, I make the intro on behalf of NYC-DSA Tech Action.

Tech Left /

I make an appearance in this article plugging the NYC Democratic Socialists of America working group I co-organize on politics and tech.